Genghis Khan and the making of the mordern world by Jack Weatherford

It’s often said that “Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World” by Jack Weatherford is a book that many billionaires read. My perception of Genghis Khan was profoundly challenged and transformed by this book. I started reading it after my wife, who discovered its popularity among influential leaders, kept praising it while she read. Intrigued by her enthusiasm, I decided to delve into it myself.

Jack Weatherford, a renowned historian, embarked on a journey across modern-day Mongolia to uncover more about Genghis Khan, including the mystery of his burial site. The Mongols were not known for documenting their history extensively, and much of what we know about Genghis Khan today comes from “The Secret History of the Mongols,”. It is the oldest surviving literary work in the Mongolian language. Written for the Mongol royal family some time after the death of Genghis Khan in 1227, it recounts his life and conquests

As someone who enjoys reading history books, I found Weatherford’s narrative style to be on another level. He weaves the story so captivatingly that it feels more like a gripping novel or a vivid film. Before reading this book, I had always pictured Genghis Khan as a brutal tribal warrior who ruled over the largest landmass ever conquered. But the reality was far more nuanced, and I was up for a surprise.

In this blog, I want to share some key insights from the book, highlighting how the rule of Genghis Khan was different from any other ruler and how the Mongol Empire contributed to shaping the modern world as we know it.

“There is no good in anything until it is finished.”

– Genghis Khan

The Rule of Genghis Khan: A New Kind of Governance

After uniting the Mongol tribes and becoming the Great Khan, Genghis Khan established a unique set of laws that were unlike any seen before. Unlike rulers who claimed divine right or adhered strictly to traditional legal systems, he crafted his own “Great Law,” a common code that applied to all under his rule.

Instead of imposing a rigid, centralized system, Genghis Khan allowed local groups to follow their traditional laws as long as they did not conflict with the Great Law.

One of the earliest and most notable laws he enacted was the prohibition of kidnapping women, signaling his intent to protect individual rights and maintain social stability. Genghis Khan also recognized the disruptive potential of religious conflicts. In a groundbreaking decree, he granted complete religious freedom, a concept unheard of in many parts of the world at that time.

This progressive legal framework emphasized that the Great Law applied equally to all, including the rulers themselves. Unfortunately, his successors adhered to this principle for only about fifty years before it was largely abandoned.

Genghis Khan’s Lessons on Leadership

Genghis Khan’s leadership principles, often imparted during moments of frustration with his own sons, are still relevant today. Here are key lessons he shared:

- Self-Control: He emphasized mastering pride, stating, “If you can’t swallow your pride, you can’t lead!” True leadership required humility and self-awareness.

- Action Over Words: A leader should demonstrate his vision through actions, not just words. Genghis warned against excessive talk and urged his sons to speak only when necessary.

- Vision and Planning: “Without the vision of a goal, a man cannot manage his own life, much less the lives of others,” he said, highlighting the importance of having clear goals and a strategy to achieve them.

- Avoiding Complacency: He cautioned against the distractions of luxury and comfort, reminding his sons that indulging in such things would make them “no better than a slave,” ultimately leading to failure.

- Conquering Hearts, Not Just Land: Perhaps his most profound lesson was the distinction between conquering an army and conquering a nation. True conquest required winning the hearts of the people, not just military victories. Yet, he also advised that the Mongol Empire should avoid uniting conquered peoples, suggesting they should be managed separately to maintain control.

Genghis Khan: The Man Behind the Legend

A glimpse into Genghis Khan’s self-perception can be found in a letter he sent to a Taoist monk on the eve of his campaign against the Muslim world. Despite his immense power, he credited his success more to the weaknesses of his enemies than to his own abilities. “I have not myself distinguished qualities,” he remarked humbly, attributing the downfall of other civilizations to their “haughtiness and extravagant luxury.”

Despite his wealth and power, Genghis Khan maintained a simple lifestyle. “I wear the same clothing and eat the same food as the cowherds and horse-herders. We make the same sacrifices, and we share the riches,” he wrote. His distaste for luxury and his commitment to moderation shaped the way he governed, treating his subjects as his children and talented individuals as his brothers, regardless of their origins.

Genghis Khan saw his mission as more than just conquest; it was a “great work” to unite the world under a single empire. He sought to create a global order that transcended traditional boundaries, setting the stage for what would later contribute to a more interconnected modern world.

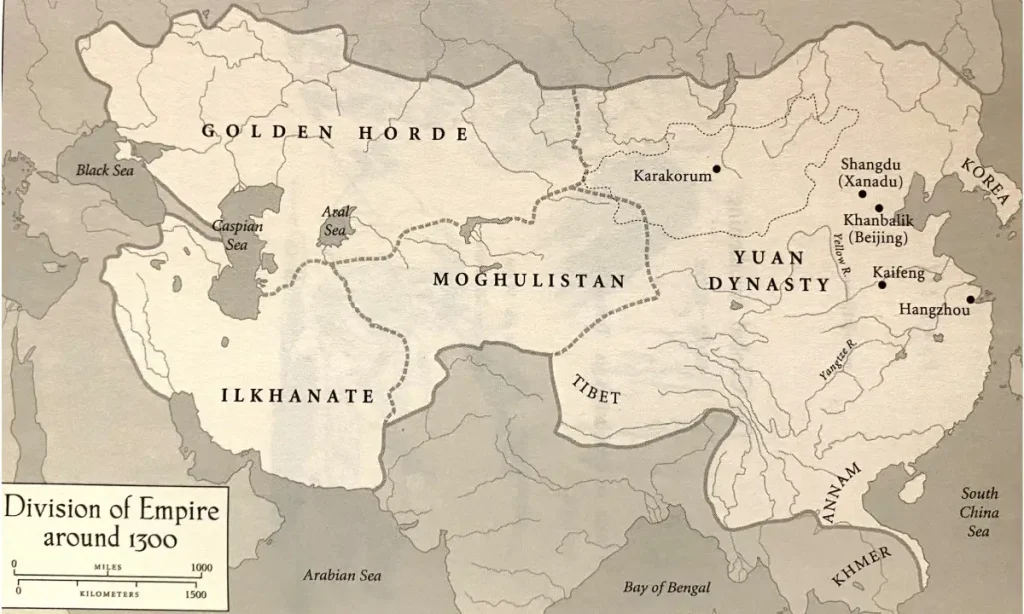

The Division of the Mongol Empire: Four Successor States

After the death of Genghis Khan, the vast Mongol Empire was divided into four main regions, each governed by his descendants. This division marked the beginning of a new era of political administration that allowed the empire’s influence to spread across continents:

-

Khubilai’s Domain: Khubilai Khan, Genghis Khan’s grandson, ruled over China, Tibet, Manchuria, Korea, and eastern Mongolia. Under his leadership, the Yuan Dynasty was established in China, reflecting a blend of Mongol and traditional Chinese governance.

-

The Golden Horde: This part of the empire governed the Slavic regions of Eastern Europe, extending Mongol influence into the heart of Europe. The Golden Horde facilitated trade and cultural exchange between Europe and Asia, impacting the region’s development for centuries.

-

The Ilkhanate: Ruled by Hulegu, another grandson of Genghis Khan, the Ilkhanate spanned from Afghanistan to Turkey. It became a melting pot of cultures, particularly fostering the resurgence of Persian culture after centuries of Arab dominance. This region laid the cultural foundations for what is modern-day Iran. Under Hulegu’s command, the Mongols achieved what no other forces had managed in centuries—they conquered the heart of the Arab world. They took control of Baghdad, a city that had been the center of Islamic civilization, and extended their influence across the region. Remarkably, no other non-Muslim forces would control Baghdad or Iraq until the American and British invasion in 2003.

-

Moghulistan: The most traditional Mongols remained in the central steppes, now known as Moghulistan. This region stretched from Kazakhstan and Siberia in the north, across Turkistan in Central Asia, down to Afghanistan in the south. It preserved the nomadic way of life that was central to Mongol identity.

Khubilai Khan: Reforming Governance in China

Under Khubilai Khan, the Mongols sought to reform many aspects of governance in China. Unlike contemporary practices in Europe, where torture was widely used, Mongol law in 1291 required substantial evidence before applying torture to elicit confessions. The legal code emphasized reason and analysis, a progressive stance compared to the expanding use of torture by both church and state in Europe at that time.

Khubilai also restructured the administrative system. Despite the traditional reliance on mandarins selected through rigorous exams, he abolished this system, preferring a diverse mix of officials. He appointed administrators from various ethnicities, including Muslims, Tibetans, Persians, and even Europeans like Marco Polo. This approach prevented overdependence on any single group and promoted cooperation among different cultures and religions.

True to the Mongol ethos established by Genghis Khan, Khubilai prioritized skills over birthright. He promoted capable individuals from humble roles, such as scribes and cooks, to positions of authority, creating a more meritocratic and dynamic administration.

Education & Literacy: Advancements Under the Mongols

Khubilai Khan’s reign marked a groundbreaking shift in education. Unlike previous dynasties, which reserved learning for the elite, Khubilai sought to provide universal education, establishing public schools that welcomed all children, including those of peasants. By making education accessible during the winter months, when peasant children were less occupied, the Mongols aimed to uplift the general population. Teachers used the colloquial language for practical lessons, breaking away from traditional classical Chinese, and according to records, Khubilai’s administration established over 20,000 public schools.

This commitment to education was remarkable for its time, as no other country had attempted such a widespread effort. In Europe, it would take another century before writers began producing works in the common language, and nearly five hundred more years before governments took responsibility for public education on a similar scale.

The Impact of Literacy

The importance of literacy was evident in other advanced civilizations of the time. Muslim lands, which encompassed Arabic, Turkic, and Persian cultures, boasted the highest levels of literacy in the 13th century. Unlike Europe and India, where only priests and select bureaucrats were literate, most villages in the Muslim world had individuals who could read and interpret religious texts. The widespread literacy in these regions fostered sophisticated commerce, technology, and culture, creating a near world-class civilization.

Innovations in Mathematics and Administration

To support the vast empire’s administration, Khubilai founded institutions like the Academy for Calendrical Studies and printing offices to produce calendars and almanacs. This period saw a surge in the need for advanced numerical skills to manage new agricultural practices, censuses, and astronomical demands. Mongol administrators sought efficient methods to handle complex calculations, often borrowing innovations from Arabic and Indian mathematics, which surpassed traditional European and Chinese methods in practicality. The abacus became a vital tool, enabling quick calculations and efficient data management across the empire.

The Power of Printing

The Mongols understood that knowledge needed to be disseminated widely, and they embraced early printing technology to achieve this. As early as 1236, Ogodei Khan had ordered the establishment of regional printing facilities across northern China. Khubilai further expanded this initiative by setting up printing offices in 1269, encouraging not only the production of government documents but also religious books, novels, and educational pamphlets.

Under Mongol rule, the volume of printed materials surged, driving down costs and making books more accessible. This included a wide array of subjects—from agriculture and medicine to laws, history, and poetry—printed in multiple languages. By adopting and expanding printing technology, the Mongols enabled a flow of information that supported administration, education, and cultural exchange across their vast empire.

Religious Tolerance: A Unique Approach to Faith Under the Mongols

The Mongols were known for their love of competition, and they applied this same spirit to religious debate. Rather than suppress differing beliefs, they encouraged open dialogue among rival religions. These debates began on a set date, overseen by a panel of judges. Religious scholars from various faiths competed using only words and logic. At the end of these debates, if no one could persuade the others, the participants often resolved their differences in typical Mongol fashion—by drinking together until they could no longer continue.

This open-mindedness was in stark contrast to the religious conflicts elsewhere in the world. While clerics engaged in civilized debates at Karakorum, religious authorities in other regions, particularly in Europe, were engaging in violent suppression. For instance, during the same period, King Louis IX of France ordered the burning of thousands of Talmudic and Jewish hand written manuscripts. Meanwhile, the Catholic Church, having failed to conquer the Holy Land, turned to suppressing religious diversity within its territories, sanctioning the torture of people suspected of heresy.

Mongke Khan’s words to a French envoy captured the Mongol philosophy on religion: “It is proper to keep the commandments of God… but how shall we arrive at concord?” The Mongol response was to bring all religions under the umbrella of the state, believing that true religious harmony could only be achieved when no single faith dominated over others. This pragmatic approach allowed the Mongol Empire to govern over a diverse set of beliefs, promoting a kind of religious tolerance rare for its time.

Commerce: Innovations That Shaped Global Trade

The First Use of Paper Money

Genghis Khan introduced the concept of paper money backed by precious metals and silk shortly before his death in 1227. This early form of currency grew under the Mongol Empire, but it was Mongke Khan who recognized the need for regulation. In 1253, he established a Department of Monetary Affairs to standardize and control the issuance of paper money, ensuring its value remained stable and preventing inflation. This shift allowed the Mongols to simplify trade by moving money rather than physical goods across their vast empire, setting a precedent for a standardized unit of currency from China to Persia.

From Warriors to Shareholders in Global Markets

During Khubilai Khan’s reign, the Mongol Empire transitioned from being a military power to a commercial powerhouse. The Mongols maintained trade routes across their territories, creating a network of relay stations stocked with supplies every 20-30 miles. These stations provided merchants with animals, guides, and accommodations, facilitating the movement of goods across difficult terrains. Travelers like Marco Polo marveled at the luxurious provisions available, reflecting the Mongols’ commitment to trade.

Early Passports and Credit Cards

To further encourage trade, the Mongol authorities introduced the paiza, a tablet made of gold, silver, or wood, which served as a combined passport and credit card. The paiza indicated the traveler’s rank and importance, ensuring safe passage, accommodation, and exemption from local taxes throughout the empire. This innovation allowed for unprecedented freedom of movement and security for traders.

Advancing Cartography

Khubilai Khan’s reign saw significant advances in mapping and cartography. In 1281, he launched an expedition to map the Yellow River, which opened new trade routes from China to Tibet. Mongol scholars synthesized knowledge from Chinese, Arab, and Greek sources to produce some of the most accurate maps of the time. Under the guidance of Arab geographers, they even constructed terrestrial globes, which depicted continents beyond Asia, reflecting their understanding of global geography.

Water Trade Routes: A Strategic Move

Understanding the efficiency of water transport over land, Khubilai Khan prioritized the use of ships for moving goods. This shift led to improvements in navigation, including the use of compasses and the production of detailed nautical charts. The Mongols established trading posts along the Black Sea, encouraging foreign merchants, like the Genoese, to set up stations. These strategic outposts allowed goods to flow more directly to European markets, bypassing longer overland routes. To protect these trade networks, the Mongols actively hunted down pirates and robbers, ensuring a secure environment for commerce.

Public Welfare: Agriculture and Healthcare

Agricultural Reforms

In 1261, Khubilai Khan established the Office for the Stimulation of Agriculture, led by eight commissioners dedicated to improving the lives and productivity of farmers. This initiative aimed not only to boost crop yields but also to ensure the overall welfare of the peasant population. By focusing on agricultural development, the Mongols sought to create a stable and prosperous society where even the most rural communities could thrive.

Advancements in Healthcare

The Mongols promoted a unique blend of medical knowledge by encouraging collaboration among practitioners from diverse backgrounds. They recognized the advanced surgical techniques of Muslim doctors and the detailed anatomical understanding of Chinese healers, based on their studies of executed criminals. To foster an exchange of expertise, Khubilai Khan established hospitals and training centers in China that brought together doctors from India, the Middle East, and local Chinese practitioners.

Additionally, Khubilai founded a department for the study of Western medicine under the guidance of a Christian scholar, further broadening the scope of medical knowledge. The Mongols also established a House of Healing near Tabriz, which served as a hospital, research center, and training facility, blending the best medical practices from both Eastern and Western traditions.

Cultural Flexibility and Local Autonomy

Unlike many empires throughout history, the Mongols did not seek to impose their own way of life on the territories they conquered. Where other conquerors, such as the Romans, British, or Spaniards, left behind a distinct cultural and architectural imprint, the Mongols maintained a remarkably light touch. Empires like Rome spread their language, gods, and even agricultural preferences, erecting identical structures from city to city, while the British built Tudor-style buildings across India, and the Spaniards left their mark from Mexico to Argentina.

In contrast, the Mongols did not attempt to force their language, architecture, or lifestyle upon their subjects. They did not impose the cultivation of unfamiliar crops, nor did they demand radical changes to the everyday lives of the people they ruled. For the most part, the Mongols forbade non-Mongols from learning their language, ensuring that they did not disrupt the cultural practices of the regions they governed. This approach allowed local traditions to flourish under Mongol rule, without the pressure to assimilate into a foreign culture.

Even in their economic strategy, the Mongols diverged from the norm. Traditional empires often funneled wealth into a single capital city—like Rome, Babylon, or Beijing—making these cities synonymous with the empires themselves. The Mongol Empire, however, operated without a centralized capital. Goods, people, and ideas flowed freely across the vast expanse of the empire, echoing the mobility and flexibility of their nomadic heritage. This movement fostered a unique kind of interconnectedness, one that facilitated the exchange of goods and cultures across continents without requiring uniformity.

The Great Wall of China: Isolationist Shift

After the Ming dynasty overthrew Mongol rule, they sought to erase Mongol influence by expelling foreigners and rejecting their open trade policies. The Ming rulers banned foreign travel, burned their ocean vessels, and directed resources to build massive walls. This isolationist approach led to the expansion of what became the Great Wall of China, marking a sharp shift from the openness of the Mongol era.

Columbus and Origin of the Term “American Indian”

In 1492, Columbus set sail westward, aiming to re-establish trade with the Mongol Empire, which he believed still existed. Unaware of the empire’s fall, Columbus thought he could reach the Mongol court by sea. Upon arriving in the Caribbean, he believed he was near the Mongol lands described by Marco Polo and assumed he had reached the outskirts of India. Thus, he called the native people “Indians,” a name that has persisted ever since.

The Mughals in India: Akbar’s Reign

The Mughals, descendants of Timur and tracing lineage to Genghis Khan’s son Chaghatai, established their rule in India under Babur in 1519. The empire flourished under Akbar (1556–1608), who shared Genghis Khan’s administrative acumen and emphasis on trade. Akbar abolished the jizya tax on non-Muslims, organized the military based on traditional Mongol units, and established a merit-based civil service. He promoted religious harmony, attempting to blend various faiths into a universal belief system called Din-i-Ilahi, and elevated the status of women, contributing to India’s rise as a global trade powerhouse.

The European Renaissance: Legacy of the Mongol Empire?

In 1620, English scientist Francis Bacon highlighted three key technological innovations—printing, gunpowder, and the compass—that shaped the modern world. These technologies, spread to Europe during the Mongol Empire, laid the foundation for the European Renaissance. While often seen as a revival of Greco-Roman culture, the Renaissance was, in many ways, a transformation of innovations and knowledge disseminated by the Mongol Empire, adapted to European needs and culture.

Modern Perception of Genghis Khan

By the 14th century, the Mongol stronghold in Central Asia had fallen under Timur, a ruler known for his ruthlessness and public torture. His brutal practices were retrospectively attributed to Genghis Khan, contributing to the negative image of the Mongols. In 1755, Voltaire’s play The Orphan of China played a key role in shaping this perception. The character of Genghis Khan concludes the play by asking, “What have I gained by all my victories, by all my guilty laurels stained with blood?” Voltaire answers, “The tears, the sighs, the curses of mankind.” With these lines, Voltaire initiated the modern cursing of Genghis Khan and the Mongols.

Following Voltaire, many playwrights and authors furthered this portrayal, depicting Genghis Khan and his empire as barbaric and fearsome tribes. Despite this enduring negative image, the profound impact of the Mongols on the modern world remains undeniable.

A Global Culture and the Foundation of the Modern World

The Mongol Empire’s approach to governance was marked by a persistent universalism, reflected in their policies on religion, writing systems, trade, and knowledge dissemination. Without a rigid cultural system to impose, the Mongols adopted and integrated practices from diverse civilizations, implementing pragmatic solutions that transcended local traditions. They prioritized what worked best, spreading effective systems of technology, agriculture, and knowledge across their vast empire.

Unlike other empires, the Mongols did not have to align their innovations with religious or cultural doctrines, allowing them to break the monopolies on thought held by local elites. This lack of cultural preference helped them foster a global culture, setting the stage for a world system based on principles of free commerce, open communication, secular politics, and religious coexistence.

Long after the empire’s decline, this global culture continued to evolve, forming the foundation of the modern world and its emphasis on international law, shared knowledge, and diplomatic immunity.

Subscribe to receive new posts

Book Review: Why I am an Atheist By Bhagat Singh